The Harrowing Haze of Heraldry

While researching this blog post, Google suggested the joke “Why do heralds not pun?” The answer? “They just cant.”

Don’t worry, I don’t understand it either. Heraldry is a famously complex system, with hundreds of rules that are strictly enforced by the College of Arms. Should an individual be granted the right to obtain a coat of arms, they still face the dizzying task of creating a unique coat of arms—one that doesn’t copy one of the over 30,000 designs currently in existence.

A tour of Agecroft Hall will reveal a number of coats of arms hidden around the house. William Dauntesey’s portrait particularly highlights his coat of arms as a proud display of his heritage, with bold yellow and red colors. But do you know how to speak the language?

Portrait of William Dauntesey (1566). Photo by Caroline Hubert.

Heraldry traces its beginnings to the 12th century, when nobles would paint their shields in order to identify themselves in jousting tournaments and battle. Nobles typically chose bold, symbolic designs that were somewhat simple in nature for ease in identification. The need for a system to exercise control over the designs quickly grew and heralds were chosen to enact rules and control the ever-increasing demand for new designs to offer the nobility. Heralds were already used to act as messengers and thus, had a vested interest in the ability to identify a noble through an assigned symbol. Due to these early, medieval origins, many heraldic terms were drawn from Norman French, Anglicized Latin, and Old English—creating a vocabulary that can feel a bit daunting to a novice heraldic enthusiast.

Every coat of arms begins with the background color, and there are technically nine options. Red is known as ‘Gules’, blue is ‘Azure’, green is ‘Vert’, black is ‘Sable’, and purple is ‘Purpure.’ Additionally, there are two ‘metals,’ gold and silver, that are known respectively as ‘Or’ and ‘Argent,’ and two ‘furs,’ referring to ‘Ermine’ (the color of the fur of stoats) and ‘Vair’ (representing the color of squirrel skins).

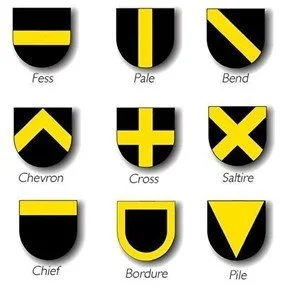

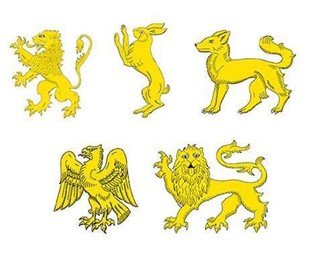

Next, we have the ‘ordinaries’—referring to the shapes found on the shields of the coat of arms. There are nine basic designs, including: Fess, Pale, Bend, Chevron, Cross, Saltire, Chief, Bordure, and Pile (see the diagram below). The use of an ordinary is optional, as you may also use a charge. A charge can be a symbol, such as a fleur-de-lis, or an animal. Animals are often thought to symbolize different qualities that a noble may want attributed to their family. For example, lions are thought to symbolize bravery, dogs represent faithfulness, stags refer to wisdom, and badgers represent endurance. Should the noble family desire something a bit more fantastical, there are also dragons, for cunning, and griffins, which represent watchfulness. Now, I hear you asking, “But does the position in which the animal is shown matter?” And the answer is “Of course!” If the lion is rearing up, it is ‘rampant,’ but if it is walking along, it is ‘passant’ (see the diagram below for the options.)

As I previously mentioned, it is very important that the coat of arms be unique to each individual. A family’s coat of arms descends through the male line of the family, meaning that the son’s coat of arms will mimic his father’s coat of arms. Should a father have more than one son, the College of Arms would add cadency symbols to the shields of the sons—indicating the order of seniority for each son. Daughters are not part of the cadency rule, but they are allowed to display their father’s coat of arms on a lozenge, or diamond-like shape. A coat of arms can also be split, should a noble wish to display the different families which make up their lineage. The best example of a quartered shield on a coat of arms, however, likely belongs to His Majesty King Charles III.

Coat of arms belonging to King Charles III

The large animals on either side of the shield are known as supporters, with the lion representing England and the unicorn representing Scotland. The first and fourth quarters depict ‘Gules three passant guardant lions in pale Or’ for England, while the second quarter shows ‘Or a lion rampant Gules armed and langued Azure within a double tressure flory-counter-flory of the second’ for Scotland, and the third quarter representing Ireland, ‘Azure a harp Or stringed Argent.’ For the British royal family, the motto is included below the shield, reading “Dieu et mon droit,” or “God and my right.” The plants shown around the motto are the symbolic Tudor Rose, Thistle, and Shamrock—again representing England, Scotland, and Ireland. While a number of changes have occurred over the centuries, England’s use of the three golden lions on a red shield stretches back to Richard I’s Great Seal in the twelfth century. There is a seemingly endless amount of information left to discover in heraldry. Records from the College of Arms mean that we can clearly trace the history of every noble family’s coat of arms, and the evolution of British nobility over centuries. The strict rules which govern its use and design make the coat of arms uniquely certain and identifiable. While the task of decoding these symbols may feel insurmountable, there are many clues to be found hiding in plain sight.

Works Cited

Brooke-Little, J.P. Royal Heraldry: Beasts and Badges of Britain. Derby: Pilgrim Press Ltd, 1977.

“The Arms of His Majesty King Charles III.” The Royal Mint. https://www.royalmint.com/shop/limited-editions/the-coat-of-arms-of-his-majesty-king-charles-iii/

“Our Guide to Heraldry.” English Heritage. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/guide-to-heraldry

“Granting of Arms.” College of Arms. https://www.college-of-arms.gov.uk/services/granting-arms

“About Heraldry.” The Heraldry Society. https://www.theheraldrysociety.com/about-heraldry/