True Crime in the Tudor Era

Looking for a true crime story? Today, it seems your options are limitless. The number of documentaries, podcasts, and books available at your fingertips seems ever increasing. Critics of the true crime genre argue that the subject has recently increased in popularity because of humanity’s growing desensitization to violence and point to an increase in morbid curiosity. Public fascination with true crime, however, is anything but new. Violent murder ballads, printed anthologies of homicidal violence, public punishments, and executions attended by thousands were all part of daily life in Tudor England, and rulers depended on it.

Pamphlets functioned much like today’s tabloids. Full of lurid details and cheap to produce, they appealed directly to the hard-working masses who were eager to focus on the misfortunes of others and leave their own troubles behind. In 1566, Thomas Harman produced a series of pamphlets known as, A Caveat for Common Cursitors Vulgarly Called Vagabonds, that catalogued a number of criminal types and their trades, such as ‘priggers of prancers,’ or horse thieves, and ‘bawdy-baskets,’ who were female thieves disguised as trinket sellers. While Harman claimed that his pamphlets empowered the public by exposing criminal secrets, his pamphlets were incredibly popular with the masses.

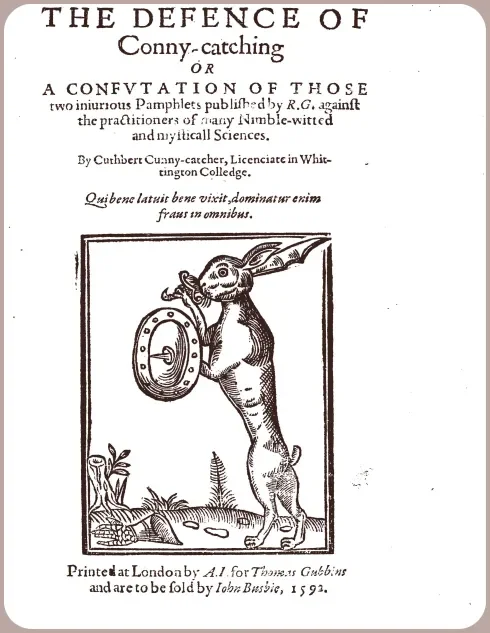

Several years later, the 1590s witnessed Robert Greene’s pamphlets, including A Noteable Discovery of Coosnage, that started his trilogy on the con games and methods employed by con men, or ‘cony-catchers.’ These pamphlets also printed graphic ballads, in which grisly scenes were paired with a jaunty tune. One ballad of a ‘monster mom,’ described a child-slaying with the lyrics, “This Emma Pitt was a schoolmistress, Her child she killed we see,/ Oh mothers, did you ever hear/ Of such barbarity?” The lyrics conclude with a stomach-churning account of the child’s death that could startle even the most avid true crime fan.

The title page of Greene’s sequel to A Noteable Discovery of Coosnage, The Defence of Conny-Catching.

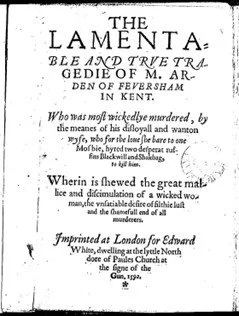

True crime authors, such as Truman Capote and Ann Rule, can find their predecessors as early as the sixteenth century. In 1592, the nonfiction play Arden of Faversham was published by an anonymous author, detailing the gruesome murder of Thomas Arden by his wife Katie in 1551. A similar work was published in 1612 by John Webster, who detailed the murder of Vittoria Accoramboni in Padua, Italy—calling his work, The White Devil. These nonfiction novels demonstrate the immense public fascination with true crime. While the pamphlets offered a quick, lurid snapshot of the story, there was a pressing demand for more information, and more insight that could also appeal to upper classes, who felt somewhat superior to the majority of crime pamphlets meant for the common citizen.

The title page for Arden of Faversham and the house where the murder occurred in 1551.

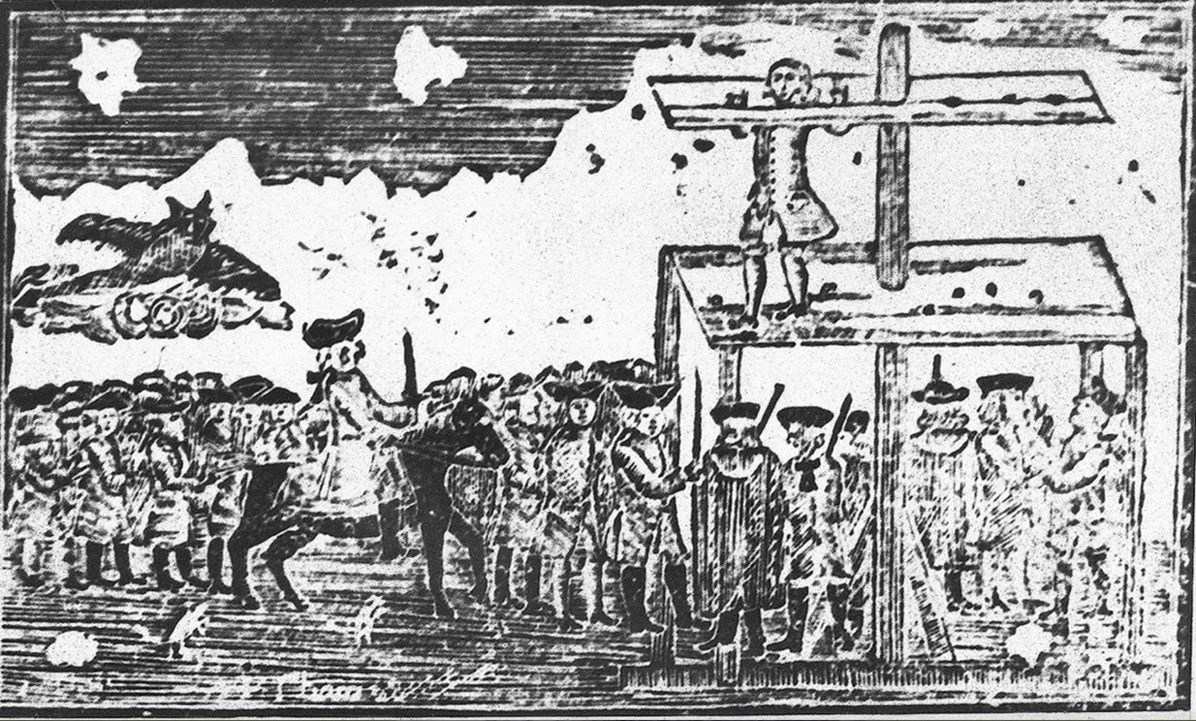

Pamphlets and plays typically focused on the most heinous crimes in order to shock their readers. Crimes such as extortion, fraud, perjury, theft, and vagrancy were assigned punishments in the public arena. Public punishments were part of daily life during the Tudor era. For cities with larger populations, officials would set up revolving platforms in which criminals could be locked inside, with their head and hands protruding. The criminal could be confined for hours or days, based on the perceived severity of their crime. Confining structures during the Tudor era ranged from cages to stocks and pillories. Stocks would confine a criminal in a seated position, but a pillory forced an individual to stand in a bent position.

While confining a body in this position would certainly be uncomfortable, the true punishment was in the criminal’s humiliation. Crowds of citizens would gather at the platforms to mock and abuse the criminals—throwing rotten eggs, dead carcasses, mud, and even stones at any criminals locked in stocks. These events would have a festival-like air, with people standing in line for hours to obtain the best viewpoint of the abuse. Officials of the time believed that the severe humiliation endured by the criminal would deter them from further illegal acts. While larger cities had more fanfare, public embarrassment was most effective in smaller villages and rural towns where the criminal was known to the crowd, and thus ridiculed by their own friends and neighbors. As the criminal was locked in the stocks or pillory, a description of their crime would be attached to their forehead to encourage crowd participation in the humiliation.

Woodcut showing a pillory being used for the punishment of a man accused of passing counterfeit money.

Tudor England’s fascination with true crime is far from complete. Tune in next month for part two, where we’ll delve into public executions and more!

Works Cited

Swinden, Cara. “Crime and the Common Law in England, 1580-1640.” University of Richmond, 1992.

Greenberg, Marissa. “Metropolitan Tragedy: Genre, Justice, and the City in Early Modern England.” University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Coursey, Sheila. “Two Lamentable Tragedies and True Crime Publics in Early Modern Domestic Tragedy.” Comparative Drama, Vol. 53, No. ¾, 2019.

Schechter, Harold. “Our Long-Standing Obsession with True Crime.” Creative Nonfiction, No. 45, 2012.

Campisi, Megan. “The Strange, Sordid World of Elizabethan -Era True Crime.” Crime Reads. April 7, 2020.

Wall, Alison. Power and Protest in England, 1525-1640. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Hazardous History. Cheltenham, UK: English Heritage, 2006.

Soaft, Lucy. “Tudor History: Complete Overview of the Dynasty that Shaped England.” The Collector. March 2, 2022.