True Crime in the Tudor Era: Part 2

A crowd with hundreds of people screaming and cheering as stern-faced guards lead a man on to a stage above the clamoring townspeople, a preacher reading aloud from a bible as a hanging rope sways in the wind. Movies and television shows by the hundreds have shown this scene, so much so that the idea of a public execution has become somewhat fantastical. In modern society, the notion of a public execution is met with repulsion. How could hundreds of people view the death of a human being as entertainment? In comparison, modern-day true crime documentaries seem tame.

For thousands of years, public executions were carried out to provoke reactions from all who witnessed the event. Governments and lawmakers used these executions to inspire harsh disapproval for the criminal and invoke a fearful respect for the law-making individuals capable of condemning a man to death. Rulers of the Tudor era mastered public punishments and executions, taking advantage of the public’s fascination with crime to create show-stopping spectacles with long lasting effects for all who bore witness, including the occupants of Agecroft Hall.

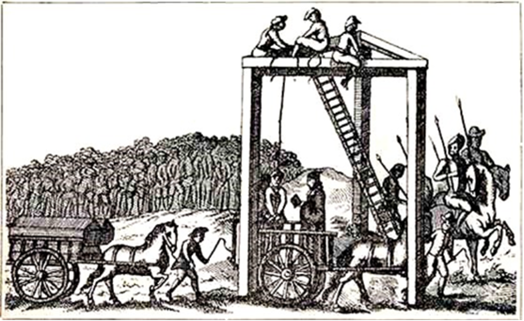

The Execution of Guy Fawkes’. Claes Janz Visscher. Engraving. 16th Century.

During the reign of King Henry VIII, approximately 70,000 were executed as a result of the death penalty. While both common people and nobility were subject to execution, class played a significant role in the chosen method of killing. Beheading was often saved for nobility, while commoners were often subject to hanging.

Nobility were often offered a modicum of privacy, in that public executions were typically reserved for lower classes. However, there were always exceptions. Nobles who escaped a public death were often still subject to public scrutiny when their heads were impaled upon a spear atop the gate of London Bridge.

Apart from nobility, the nature of the crime and the sex of the offender were the other determinants of execution method. Crimes of treason were taken most seriously, with a typical sentence of ‘hanged, drawn, and quartered.’ This execution required the criminal to be publicly hanged, removed from the gallows, disemboweled, and then cut into pieces—a feat often reached by tying limbs from the body to four different horses who were then sent running in different directions. This method of execution was seen as inappropriate for women found guilty of treason, due to the nudity involved. They were instead sentenced to burning at the stake.

The severity of these capital punishments could be lessened by a merciful executioner, who had the ability to strangle a woman before she was burned or allow a man to fully die by hanging before his body was removed and disemboweled. However, these mercies were often subject to the demands of violence from a ruthless crowd of spectators.

Tyburn Tree. Illustration. 1680.

While smaller cities and villages in England erected temporary scaffolds to execute their convicted people, London had two permanent gallows installed in Smithfield and Tyburn, the latter being at the edge of the city’s boundaries.

The Tyburn Tree, erected in 1571, was a special form of gallows that included a horizontal wooden triangle supported by three legs. This allowed multiple criminals to be hung at once. In 1649, 24 criminals were hung simultaneously, making Tyburn the preferred site for mass executions.

Tyburn also included public stands for the crowds of thousands looking to witness the event after it was advertised in the popular newspaper, The Newgate Calendar. Members of the crowd would fight for a position with the best view, and even line up overnight.

Executions developed a carnival-like atmosphere, with vendors selling food and memorabilia—such as pieces of the convicted person’s clothing or possessions. Once the body was cut down, the crowd would go so frenzied as to riot, fighting amongst each other to touch the deceased or cut a lock of their hair for keeping. Should the prisoner have any family or friends within the crowd, they would often seek to protect the body from surgeons looking to practice their anatomical knowledge. The atmosphere and fervor created in these conditions generally suited rulers well.

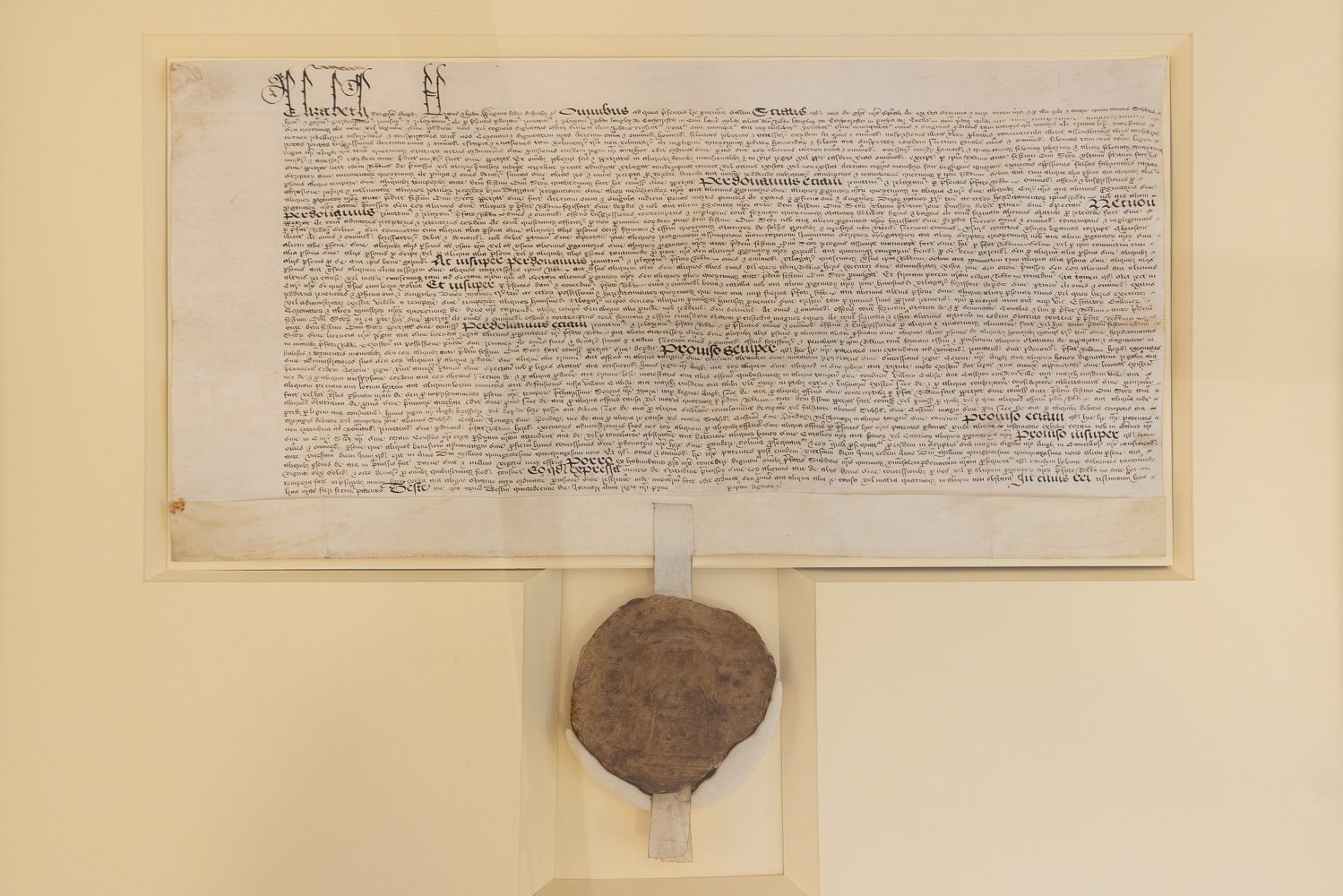

Universal Pardon to Robert Langley. January 15, 1559, Agecroft Hall & Gardens, Richmond, VA. (Photo by Caroline Hubert)

Here at Agecroft Hall, we have a rare piece of legal history from Elizabeth I’s reign. This universal pardon, purchased by Robert Langley (an original owner of Agecroft Hall), functioned as a ‘get out of jail free’ card during the Tudor era—retroactively protecting Langley, should he find himself accused of a crime.

Deeds such as these could be purchased by wealthy nobles, but commoners were not granted this luxury. Pardons could only be issued by the crown but were rare for the masses. Rulers, such as Elizabeth I, relied on the fear created by public punishments and executions.

Through their legal system and punishment of crime, rulers of the Tudor era attempted to exert control over the public masses—eliminating any who encouraged or participated in a deviant behavior that could threaten their control. Public executions allowed for a milieu of emotions to be expressed by the otherwise powerless and oppressed public. Spectators were given a figure to blame for their troubles, before watching that figure endure a horrible death, and be punished by an all-mighty authority. The government sought to deter crime and rebellious thought through the fear that this punishment could be levied on anyone. By watching the event, it allowed the public to feel as though they were participating in the punishment, and thus gain catharsis and a hint of culpability. Theoretically, the hundreds of thousands of commoners could easily overpower the limited number of nobility, and rulers took many precautions to curtail any thoughts of rebellion with these displays of public executions.

Modern day society often views public fascination with true crime as a new phenomenon and public executions as a scary, relic of the past. However, historical rulers relied on public fascination with true crime in order to maintain their rule. And the evidence of the delicate legal dance that even the wealthiest of nobles were forced to participate in has been left to the fragile parchment records of history.

Works Cited

Swinden, Cara. “Crime and the Common Law in England, 1580-1640.” University of Richmond, 1992.

Greenberg, Marissa. “Metropolitan Tragedy: Genre, Justice, and the City in Early Modern England.” University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Coursey, Sheila. “Two Lamentable Tragedies and True Crime Publics in Early Modern Domestic Tragedy.” Comparative Drama, Vol. 53, No. ¾, 2019.

Schechter, Harold. “Our Long-Standing Obsession with True Crime.” Creative Nonfiction, No. 45, 2012.

Campisi, Megan. “The Strange, Sordid World of Elizabethan -Era True Crime.” Crime Reads. April 7, 2020.

Wall, Alison. Power and Protest in England, 1525-1640. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Hazardous History. Cheltenham, UK: English Heritage, 2006.

Soaft, Lucy. “Tudor History: Complete Overview of the Dynasty that Shaped England.” The Collector. March 2, 2022.